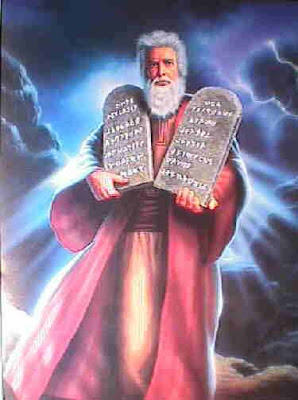

The Torah contains 613 commandments. But on Mount Sinai -- the only occasion in history when the entire Jewish people had a face-to-face meeting with God -- God chose to emphasize 10.

The first two of the Ten Commandments we heard from the mouth of God directly without Moses as an intermediary, whereas the other eight we heard through Moses.

According to many commentators the first one isn't really a commandment at all, but more in the nature of an introductory statement to all the commandments. But there is a special common denominator that unifies these 10 and sets them apart from all the others; they are the only commandments that appear on the "Tablets of the Law."

The significance of being inscribed on the tablets is explained thus by Moses:

"He (God) told you His covenant that He commanded you to observe, the 10 declarations, and he inscribed them on two stone tablets." (Deut. 4:13)

These 10 declarations have a dual aspect. Aside from being commandments in their own right like the rest of the 613, they constitute a special covenant between God and Israel. We refer to them in the Passover Haggadah as the "Two Tablets of the Covenant." It is this covenantal aspect that we propose to explore in this essay.

THE COVENANT

A covenant is not some spooky mystical bond, but merely a fancy term for a contract. Every contract is a negotiated agreement between two parties. Generally speaking, when such an agreement is reached, it is recorded and each of the parties gets a notarized copy so that they have a record of their contractual rights and obligations. By describing the Ten Commandments as a covenant, the Torah informs us that the tablets represent a copy of the contractual agreement between God and the Jewish people. The tablets we received at Sinai constitute Israel's notarized copy.

But this seems like a startling idea. In what sense can commandments, which are basically orders issued by God, be described as negotiated agreements?

To better understand the contractual aspect of these commandments, let us review the process of negotiations that led to their culmination.

THE OFFER

When Moses ascended the mount for the first time after the Jewish people encamped at its feet, God sent Moses back to the Jews with the following message:

You have seen what I did to Egypt, and that I have borne you on the wings of eagles and brought you to Me. And now, if you obey Me and keep My covenant, you shall be to Me the most beloved treasure of all peoples, for Mine is the entire world. You shall be to Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. (Exodus 19:4-6).

This speech contains God's offer.

Nachmanides explains what is being offered: The entire world belongs to God but He placed the other nations under the rule of angels. A "beloved treasure" is something that one never allows to escape from one's own careful vigilance. God offered the Jewish people His personal attention. He would attend to the affairs of the Jewish people Himself, instead of handing them over to the jurisdiction of angels as He does with other nations.

But this offer of personal Divine jurisdiction actually contains two parts. Aside from the promise of care in this world, it also offers an entry to the next world. For a treasured object never loses its value and remains permanently precious. Someone precious to God, who is eternal, will remain with God for eternity. If Israel takes up God's offer and becomes His treasured object, that automatically extends the deal into the realms of forever.

These two ideas are contained in the two phrases "a kingdom of priests," a reference to this world, and "a holy nation," which is a reference to the next. Note that the word "holy" in Hebrew always implies separation from physicality. Thus a "holy nation" is a nation in a non-physical sense, an other-worldly nation.

THE ACCEPTANCE

Moses came and summoned the elders of the people, and put before them all these words that God had commanded him. The entire people responded together and said, "Everything that God has spoken we shall do!" (Exodus 19:7-8)

This verse describes the Jewish people's acceptance of God's offer.

Moses presented the proposition to the elders so that they might circulate among the people, obtain their reactions and deliberate their response, but the people pre-empted this deliberation process by enthusiastically declaring their immediate unanimous acceptance with a single voice.

Obviously the Jews thought this was a great offer. They immediately accepted it without prior deliberation. But there must be some heavy strings attached.

Indeed there are -- the strings are the commandments themselves.

To enter the covenant you must accept the Ten Commandments. But what is so difficult about these commandments? A surface reading shows nothing controversial or difficult to observe.

Logic directs us to take a closer look at these commandments for the answer.

It is immediately apparent that they are divided into two parts. Indeed Jewish tradition teaches that there are two tablets: 1) one corresponding to obligations toward God, and 2) the other consisting of obligations toward one's fellow man. But if we examine them closely we can see that they are related.

Let us refer to the two tablets for the sake of simplicity as God's tablet and as man's tablet, and look at them in pairs.

I AM GOD / DON'T MURDER

The first commandment on God's tablet is the acceptance of God as our ruler. He took us out of the bondage of Egypt so that we might become His servants instead of the servants of Pharaoh. Parallel to this commandment on man's tablet we find the injunction against murder. The implication is clear. The act of murder represents a violation in spirit of the first commandment on God's tablet as well.

Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed; for in the image of God He made man. (Genesis 9:6)

The prohibition against murder is based on the fact that man is God's image. When you take a human life you are destroying God's image.

If a man shall have committed a sin whose judgment is death, he shall be put to death and you shall hang him on a gallows. His body shall not remain for the night on the gallows, rather you shall surely bury him on that day, for a hanging person is a curse of God... (Deut. 21:22-23)

The Talmud (Sanhedrin 46b) says that to murder a human being is akin to murdering God's twin. No greater violation of the spirit of the first commandment on God's tablet is imaginable.

HAVE NO OTHER GODS / DON'T COMMIT ADULTERY

The second commandment on God's tablet is the injunction against idolatry. On man's tablet we find the injunction against adultery.

The injunction against idols is a prohibition against obtaining God's bounty contrary to His will, by getting it second hand. The idolater wants to obtain a portion of Divine bounty not according to God's policy. As part of the grant of free will to man, God makes this possible.

The institution of marriage, whose sanctity the sin of adultery violates, is God's bounty against loneliness. The human symbol of the love that extinguishes this loneliness is the female. God explained the creation of woman thus:

It is not good for man to be alone; I will make him a helper corresponding to him. (Genesis 2:18)

God did so by splitting the human being in two, thus curing the existential angst of solitude. Both the male and female share in this bounty equally, but she is the symbol of the Divine cure. In God's scheme every marriage is designed with the idea that the partners serve as each other's complement.

Adultery is the taking of this Divine bounty against God's policy and will. This cure for the human angst was intended for a different recipient. Thus adultery parallels idolatry.

DON'T SWEAR FALSELY / DON'T STEAL

The third commandment on God's tablet is the prohibition against false oaths, which parallels the prohibition against theft on man's tablet.

God is the source of all reality. Substituting a false reality for the one that God established is a perversion of God's work. The false oath is an affirmation that God is associated with a reality that He did not intend.

Just as God is the source of all reality, He is the source of all bounty. Something intended for Reuven cannot help to sustain Shimon. If God intended it for Reuven, Shimon's appropriation of it is also a perversion of true reality.

If not for the fact that God's connection with reality is concealed by nature to allow man free choice, no one could possibly reach out his hand to take what belongs to someone else. The hand would whither as it stretched and the stolen object would disappear as soon as it landed in the wrong hand.

KEEP SHABBAT / DON'T TESTIFY FALSELY

The fourth commandment on God's tablet is Shabbat observance. Paralleling it on man's tablet is the prohibition against testifying falsely.

Sabbath observance is a testimony to God's creation. If God is the creator, He is also the source of all creative power in the world. Everything that man creates and accomplishes is in reality a channeling of God's creative power. If the world were not designed to conceal God's presence so as to allow man free will, the laws of Shabbat would be an accurate depiction of creation as it really appears. Only God creates; man merely enjoys the bounty of God's creative power.

The failure to observe the Sabbath is an act of false testimony. This false testimony claims that there is an uncreated, purposeless world with no final destination.

Bearing false witness against a fellow human being places one's fellow in a world that was not created by the channeling of God's creative power. The false witness created this alternative universe in his testimony. Thus the lack of Shabbat observance and the bearing of false witness are exact parallels.

HONOR YOUR PARENTS / DON'T COVET

The final commandment on God's tablet is to respect one's parents. Paralleling this commandment on man's tablet is the prohibition against coveting your neighbor's wife or anything belonging to your neighbor.

Instead of beginning with God's tablet and switching over to man's, let's take the opposite approach on this one.

Ibn Ezra asks a provocative question about the prohibition to covet: How is it possible to command a person not to desire something that is inherently desirable?

We can easily comprehend the prohibition against actualizing illicit desires in real life, but these prohibitions concerning actualization are already stated in the first four prohibitions on man's tablet. How can we relate to a prohibition against desire itself?

Ibn Ezra answers with a metaphor. By the rules of human nature, the peasant covets his fellow peasant's wife and not the king's daughter. When he sees the princess passing by in her carriage, even if he finds her beautiful, he does not covet her. She is beyond his reach. Any thoughts he may have about her are in the nature of pure fantasies rather than actualizable desires.

If a person is properly oriented in the world, everything that belongs to someone else is in the same relationship to him as the unobtainable princess is to the peasant. God gives everyone the things they need to have in order to successfully conduct their lives. It is not circumstance that determines what each person has; rather this is determined by Divine decisions, which are based on rational considerations of what is beneficial.

If the things that I desire are within my permitted reach, then I am entitled to assume that God placed them there deliberately, because I really can use them to achieve the goals that He set for me. If they are not within my permitted reach, I should conclude that they are not good for me to have and my only link to them is in the harmless fantasy world of my imagination.

Coveting things that belong to other people is the clearest danger signal that life is out of focus. In the world according to the Ten Commandments, every person is unique in the eyes of God; every person is a covenantal partner. Each such partner lives in his own world surrounded by the things that he specifically needs to test his commitment to the covenantal relationship, and to help him grow into his full potential as God's partner.

The world is not a jungle where we all compete for the same prize, which properly belongs according to jungle law to the swiftest and the most able. In such a world, whatever anyone else may have is a clear possibility for me as well, especially if I consider myself more fit. In the jungle world it is permissible to covet anything no matter who has it. As long as you go about taking it away from its present owner in ways that society doesn't outlaw, you are doing no wrong. The person who covets is living in the wrong world.

Moving back to God's tablet, we find the same idea expressed in the commandment to honor one's parents. This commandment has nothing to do with conventional respect and gratitude. For the majority of us who have had the good fortune to be raised in normal loving homes, the feelings of gratitude toward our parents are an inseparable part of our orientation to the world. There is no need to reinforce human nature through commandments. But the honor meant here is another matter altogether.

Honor is assigned on the basis of what you consider important in life, not on the basis of gratitude. Every person feels the pull of the brave new world out there. The lure of new ideas and different lifestyles is a very powerful force within all of us. We tend to patronize the world of our parents as being outmoded and old-fashioned. We feel the urge to spread our wings and fly off in new directions.

But the world God placed us in is the world of our parents. Three partners join forces in the creation of a person: God, his father and his mother (Talmud, Nidah 31a). God does not choose his partners at random. If He selected these particular partners, He wants the child to be subjected to their world. The values passed on by one's parents create the proper background to one's life, selected by God Himself. The parents must be honored, not merely loved.

Coveting what belongs to another and not honoring one's parents have the same common source, the belief that one is in the wrong world.

IN CONCLUSION

The predominant theme of the tablets is that it is impossible to separate one's interactions with other people from one's interactions with God. In the world of the covenant, where Israel becomes a nation of priests and a holy people, the sanctity of God spreads out to embrace all aspects of life. There is no getting away from Him.

The covenant is not about obedience to God's orders, or the adoption of certain customs and practices. The covenant is about the willingness to inhabit a common, shared world with God where every aspect and relationship in life is tinged by the fact that it takes place in His all-embracing presence. For someone who desires to live in his own space, the covenant is an intolerable burden.

It actually turns out that God's offer to make us into a nation of priests and a holy people is a double-edged sword. We must be willing to become a nation of priests and a holy people as well. This entails inhabiting a world where it is impossible to draw any distinct lines between the areas designated as sacred, and those that can be considered secular and ordinary.

We become such holy priests only by allowing the two tablets of the law to converge into a single covenantal framework. The strings attached to God's offer are the chains that bind together the secular and the sacred into a single coherent life.

sursa:www.aish.com

*****

http://www.esotericarchives.com/esoteric.htm

*****

Aseret ha-Dibrot:

The "Ten Commandments"

According to Jewish tradition, G-d gave the Jewish people 613 mitzvot (commandments). All 613 of those mitzvot are equally sacred, equally binding and equally the word of G-d. All of these mitzvot are treated as equally important, because human beings, with our limited understanding of the universe, have no way of knowing which mitzvot are more important in the eyes of the Creator. Pirkei Avot, a book of the Mishnah, teaches "Be as meticulous in performing a 'minor' mitzvah as you are with a 'major' one, because you don't know what kind of reward you'll get for various mitzvot." It also says, "Run after the most 'minor' mitzvah as you would after the most 'important' and flee from transgression, because doing one mitzvah draws you into doing another, and doing one transgression draws you into doing another, and because the reward for a mitzvah is a mitzvah and the punishment for a transgression is a transgression." In other words, every mitzvah is important, because even the most seemingly trivial mitzvot draw you into a pattern of leading your life in accordance with the Creator's wishes, rather than in accordance with your own.

But what about the so-called "Ten Commandments," the words recorded in Exodus 20, the words that the Creator Himself wrote on the two stone tablets that Moses brought down from Mount Sinai (Ex. 31:18), which Moses smashed upon seeing the idolatry of the golden calf (Ex. 32:19)? In the Torah, these words are never referred to as the Ten Commandments. In the Torah, they are called Aseret ha-D'varim (Ex. 34:28, Deut. 4:13 and Deut. 10:4). In rabbinical texts, they are referred to as Aseret ha-Dibrot. The words d'varim and dibrot come from the Hebrew root Dalet-Beit-Reish, meaning word, speak or thing; thus, the phrase is accurately translated as the Ten Sayings, the Ten Statements, the Ten Declarations, the Ten Words or even the Ten Things, but not as the Ten Commandments, which would be Aseret ha-Mitzvot.

The Aseret ha-Dibrot are not understood as individual mitzvot; rather, they are categories or classifications of mitzvot. Each of the 613 mitzvot can be subsumed under one of these ten categories, some in more obvious ways than others. For example, the mitzvah not to work on Shabbat rather obviously falls within the category of remembering the Sabbath day and keeping it holy. The mitzvah to fast on Yom Kippur fits into that category somewhat less obviously: all holidays are in some sense a Sabbath, and the category encompasses any mitzvah related to sacred time. The mitzvah not to stand aside while a person's life is in danger fits somewhat obviously into the category against murder. It is not particularly obvious, however, that the mitzvah not to embarrass a person fits within the category against murder: it causes the blood to drain from your face thereby shedding blood.

List of the Aseret ha-Dibrot

According to Judaism, the Aseret ha-Dibrot identify the following ten categories of mitzvot. Other religions divide this passage differently. See The "Ten Commandments" Controversy below. Please remember that these are categories of the 613 mitzvot, which according to Jewish tradition are binding only upon Jews. The only mitzvot binding upon gentiles are the seven Noahic commandments.

1. Belief in G-d

This category is derived from the declaration in Ex. 20:2 beginning, "I am the L-rd, your G-d..."

2. Prohibition of Improper Worship

This category is derived from Ex. 20:3-6, beginning, "You shall not have other gods..." It encompasses within it the prohibition against the worship of other gods as well as the prohibition of improper forms of worship of the one true G-d, such as worshiping G-d through an idol.

3. Prohibition of Oaths

This category is derived from Ex. 20:7, beginning, "You shall not take the name of the L-rd your G-d in vain..." This includes prohibitions against perjury, breaking or delaying the performance of vows or promises, and speaking G-d's name or swearing unnecessarily.

4. Observance of Sacred Times

This category is derived from Ex. 20:8-11, beginning, "Remember the Sabbath day..." It encompasses all mitzvot related to Shabbat, holidays, or other sacred time.

5. Respect for Parents and Teachers

This category is derived from Ex. 20:12, beginning, "Honor your father and mother..."

6. Prohibition of Physically Harming a Person

This category is derived from Ex. 20:13, saying, "You shall not murder."

7. Prohibition of Sexual Immorality

This category is derived from Ex. 20:13, saying, "You shall not commit adultery."

8. Prohibition of Theft

This category is derived from Ex. 20:13, saying, "You shall not steal." It includes within it both outright robbery as well as various forms of theft by deception and unethical business practices. It also includes kidnapping, which is essentially "stealing" a person.

9. Prohibition of Harming a Person through Speech

This category is derived from Ex. 20:13, saying, "You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor." It includes all forms of lashon ha-ra (sins relating to speech).

10. Prohibition of Coveting

This category is derived from Ex. 20:14, beginning, "You shall not covet your neighbor's house..."

The Two Tablets: Duties to G-d and Duties to People

Judaism teaches that the first tablet, containing the first five declarations, identifies duties regarding our relationship with G-d, while the second tablet, containing the last five declarations, identifies duties regarding our relationship with other people.

You may have noticed, however, that the fifth category, which is included in the first tablet, is the category to honor father and mother, which would seem to concern relationships between people. The rabbis teach that our parents are our creators and stand in a relationship to us akin to our relationship to the Divine. Throughout Jewish liturgy, the Creator is referred to as Avinu Malkeinu, our Father, our King. Disrespect to our biological creators is not merely an affront to them; it is also an insult to the Creator of the Universe. Accordingly, honor of father and mother is included on the tablet of duties to G-d.

These two tablets are parallel and equal: duties to G-d are not more important than duties to people, nor are duties to people more important than duties to G-d. However, if one must choose between fulfilling an obligation to G-d and fulfilling an obligation to a person, of if one must prioritize them, Judaism teaches that the obligation to a person should be fulfilled first. This principle is supported by the story in Genesis 18, where Abraham is communing with G-d and interrupts this meeting to fulfill the mitzvah of providing hospitality to strangers (the three men who appear). The Talmud gives another example, disapproving of a man who, engrossed in prayer, would ignore the cries of a drowning man. When forced to choose between our duties to a person and our duties to G-d, we must pursue our duties to the person, because the person needs our help, but G-d does not need our help.

The "Ten Commandments" Controversy

In the United States, a controversy has persisted for many years regarding the placement of the "Ten Commandments" in public schools and public buildings. But one critical question seems to have escaped most of the public dialog on the subject: Whose "Ten Commandments" should we post?

The general perception in this country is that the "Ten Commandments" are part of the common religious heritage of Judaism, Catholicism and Protestantism, part of the sacred scriptures that we all share, and should not be controversial. But most people involved in the debate seem to have missed the fact that these three religions divide up the commandments in different ways! Judaism, unlike Catholicism and Protestantism, considers "I am the L-rd, your G-d" to be the first "commandment." Catholicism, unlike Judaism and Protestantism, considers coveting property to be separate from coveting a spouse. Protestantism, unlike Judaism and Catholicism, considers the prohibition against idolatry to be separate from the prohibition against worshipping other gods. No two religions agree on a single list. So whose list should we post?

And once we decide on a list, what translation should we post? Should Judaism's sixth declaration be rendered as "Thou shalt not kill" as in the popular KJV translation, or as "Thou shalt not murder," which is a bit closer to the connotations of the original Hebrew though still not entirely accurate?

These may seem like trivial differences to some, but they are serious issues to those of us who take these words seriously. When a government agency chooses one version over another, it implicitly chooses one religion over another, something that the First Amendment prohibits. This is the heart of the controversy.

But there is an additional aspect of this controversy that is of concern from a Jewish perspective. In Talmudic times, the rabbis consciously made a decision to exclude daily recitation of the Aseret ha-Dibrot from the liturgy because excessive emphasis on these statements might lead people to mistakenly believe that these were the only mitzvot or the most important mitzvot, and neglect the other 603 (Talmud Berakhot 12a). By posting these words prominently and referring to them as "The Ten Commandments," (as if there weren't any others, which is what many people think) schools and public buildings may be teaching a message that Judaism specifically and consciously rejected.

sursa:Judaism 101

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu